To ensure gift delivery by 12/25, please place orders via UPS shipping no later than 12/17.

ClosePreserving a Panorama: A Conservation Journey

Have you ever stored something rolled up? Maybe that poster you bought at a concert years ago that you tucked away in the top of your closet? Rolling can help protect an item from accidentally being torn or to store it more easily. However, depending on what item you’re rolling, and depending on how long it’s stored that way, rolling, in the long run, can cause damage to that object. But thanks to the skilled work of conservators, all is not lost.

In the archival collection of the Association for Education and Rehabilitation of the Blind and Visually Impaired (AER) are several panoramic photographs. They had been stored rolled up, likely due to their long, unusual shape. However, after being stored that way for a number of years, they require professional conservation to flatten them back out to their original state. With 21 of these panoramic photographs in the collection, we opted to send one out for conservation to gauge the approximate cost for treatment for the remaining photographs.

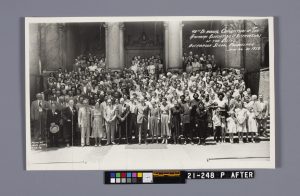

The photograph I selected for treatment had numerous creases and a few tears, so it appeared to be a good representative of the condition of the other photographs in the collection. This black and white photograph it turned out, was a large group shot from June 1950. The picture was taken at the 40th bi-annual convention of the American Association of Instructors of the Blind, at the Overbrook School in Philadelphia.

We sent the photograph to the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in Massachusetts, a company that specializes in the treatment of paper-based collections. In order to mail the photograph securely and prevent further damage during its transport, I wrapped a cardboard tube in a layer of perforated Tyvek (to provide an archival barrier over the highly acidic cardboard base). I then carefully slid the rolled photograph onto the tube, wrapped it in another layer of Tyvek, and tied both ends of the tube with cotton twill tape to keep the photograph from shifting during transport (think along the lines of a giant Tootsie Roll…). Lastly, I nestled the wrapped photograph in a box filled with packing peanuts for extra cushioning. With the help of our staff in the shipping department, we sent the box overnight and waited to hear from the conservators what their recommendations for treatment would be.

A short time later we received NEDCC’s report with their recommendations for treatment. Due to the other condition issues—namely the creases, tears, and flaking emulsion—the conservators had to do a fair bit of work to stabilize it in addition to the primary task of humidifying and flattening the photograph. After signing the agreement, our photograph was placed in the queue for treatment. Fairly quickly, I received an email saying our photograph was up next and we eagerly awaited the results. The turn-around time for the conservation work was very quick and soon we received our package. The unboxing process was fun, and it felt like unwrapping a much-anticipated present. I carefully cut the packing tape, and inside, expertly packaged, was our newly flattened and conserved photograph.

It was so exciting to finally be able to see this photograph in its entirety and examine all of the smiling faces in the picture. I knew the humidification process to flatten out the photograph was our main goal but the expert work the conservators performed was very well done, and very well hidden upon first glance. It wasn’t until I examined the detailed digital images showing the restoration process that I appreciated just how much work was performed in order to stabilize the photograph. The photograph was first humidified and flattened under pressure to return the photograph to its original, unrolled state. The vertical creases were then reinforced with toned Japanese paper and wheat starch paste, and the flaking emulsion was treated with a gelatin solution.

The conservators at NEDCC certainly restored the life back into this old photograph. Thanks to their work, they ensured that this photograph will be in the condition to be preserved for years to come in the archive here at APH. I look forward to seeing what the other 20 photographs in this collection will look like when we’ve raised the funds to have the remaining photos restored to their former glory as well. Stay tuned for future updates!

Mary Beth Williams is the Museum Collections Manager at APH.

Share this article.

Related articles

Cross-Cultural Collaboration: An Interview with Dr. Elyse Connors on Her Fulbright Trip to Lagos

International efforts in blindness often involve cross-cultural collaboration to address critical gaps in services and training. We had the pleasure...

Running a Marathon: Moving a Museum Collection

With the Dot Experience at APH officially breaking ground, we have been incredibly busy behind the scenes preparing for construction...

Finding Sadie

“The blind veterans here in the Helen Keller class are able, thru talking books, to obliterate the tedious hospital hours...