To ensure gift delivery by 12/25, please place orders via UPS shipping no later than 12/17.

ClosePhase Boxes and Flat Dots: Preserving Braille Materials in the KSB Alumni Association Collection

Our next-door neighbor the Kentucky School for the Blind (KSB) has a long and rich history, and as such has produced a vast amount of archive-worthy materials over the years. KSB was the third state-supported school for the blind in the U.S., opening its original campus in downtown Louisville in 1842. After several moves, the school ultimately found its permanent home on Frankfort Ave in 1855. The history of APH is in many ways intertwined with KSB, sharing both superintendents and their building during the early years of the company’s existence. We have a collection of KSB materials in our museum holdings, documenting various aspects of the school’s history. And as caretakers of their collection, we provide the best possible storage solutions for these unique materials.

A recent addition to our KSB Alumni Association collection is an array of school newsletters and publications. Some of the issues date back to the 1940s and include print and braille issues into the 21st century. My colleague Justin Gardner wrote about a digitization project related to this collection in his January blog: https://www.aph.org/the-kentucky-school-for-the-blind-alumni-association-archive/. Recently I’ve been working on a different aspect of this collection’s preservation—ensuring proper long-term storage of all the braille materials.

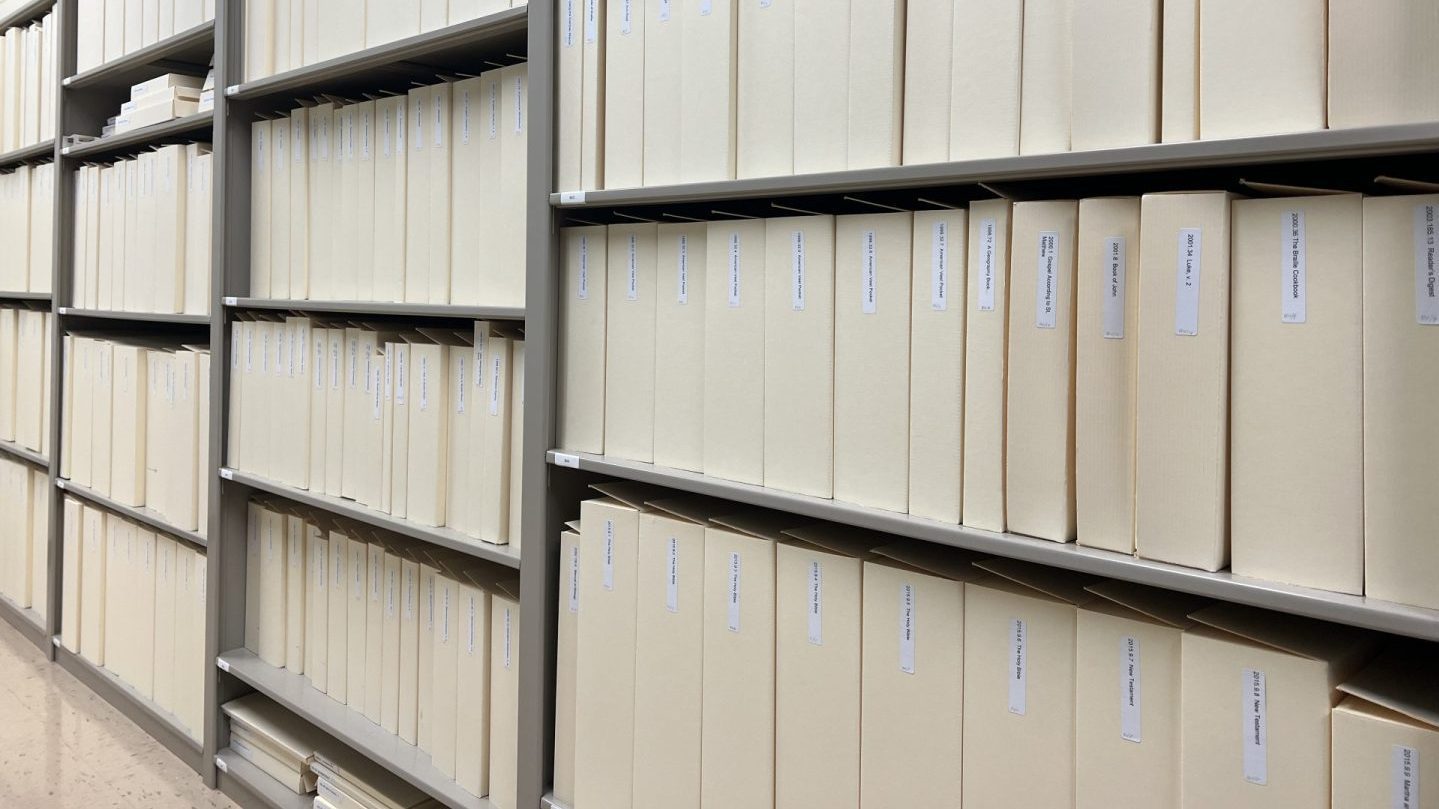

Braille—and other types of raised letter or embossed materials— require a bit of special care for their preservation. When the collection was initially cataloged, the materials were put into standard archival folders and boxes for temporary storage. Now I’m putting them into custom made individual enclosures called phase boxes. Each phase box is ordered for the specific measurements of that individual book. Each book, or stack of newsletters as in this case, is measured down to the millimeter and a box is custom cut so the box will perfectly fit the dimensions of that book. These special types of enclosures were initially designed in the 1970s at the Library of Congress to be part of a “phased” conservation approach to stabilize and protect materials in need of future conservation work. However, phase boxes are now often used as permanent storage for fragile materials. And they are an important part of our collections care practices here at APH.

Embossed materials like these newsletters are especially vulnerable to becoming flattened if proper care and protections aren’t given to them. Over time, the braille dots can become flattened if the materials are stored flat and they should never be stored with other items stacked on top. This type of damage is evident in our copy of Valentin Hauy’s Essai sur l’education des Avuegles (An Essay on the Education of the Blind) currently on display in the museum. The Essai was the first embossed book for the blind, produced in raised type and with ink applied so the raised letters could be read by both touch and sight. However, since the book was bound like a standard print book, over the years the once raised letters have subsequently become flattened to the point that all that remains are the inked letters.

We have a lot of braille and embossed materials in our collection and want to preserve their integrity and original clarity for as long as possible. By storing KSB’s embossed publications in phase boxes, we can ensure that these materials will be protected in perpetuity, and the braille dots will still clearly convey the notes and stories of KSB students, staff and faculty for many, many years to come.

If you’d like to learn more about phase boxes or if you’d like to try your hand at making one yourself, check out this YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kJyrf_u1G4

Mary Beth Williams is the Museum Collections Manager at the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

Deinstalling a Museum Exhibit

The saying “it takes a village” can be applied in any number of settings. In our case, it has truly...