To ensure gift delivery by 12/25, please place orders via UPS shipping no later than 12/17.

CloseOnline Archives in a Digitized World

Have you ever done research in an archive? Maybe for a school project, or just researching a topic of personal interest? There’s something special about visiting an archive, and burying your head in materials from a collection, hunting for that piece of information that will hopefully answer the question you’re seeking—or possibly even send your research down a completely different path. Of course, COVID-19 threw a huge wrench in that experience. And although a lot of places (including APH) are welcoming in-person researchers once again, there may be other barriers to visiting an archive. Maybe the archive isn’t located nearby, or you just need to look up one thing and don’t need to search through the entire collection. While nothing can replace the experience of in-person research, there are a lot of practical benefits of online resources.

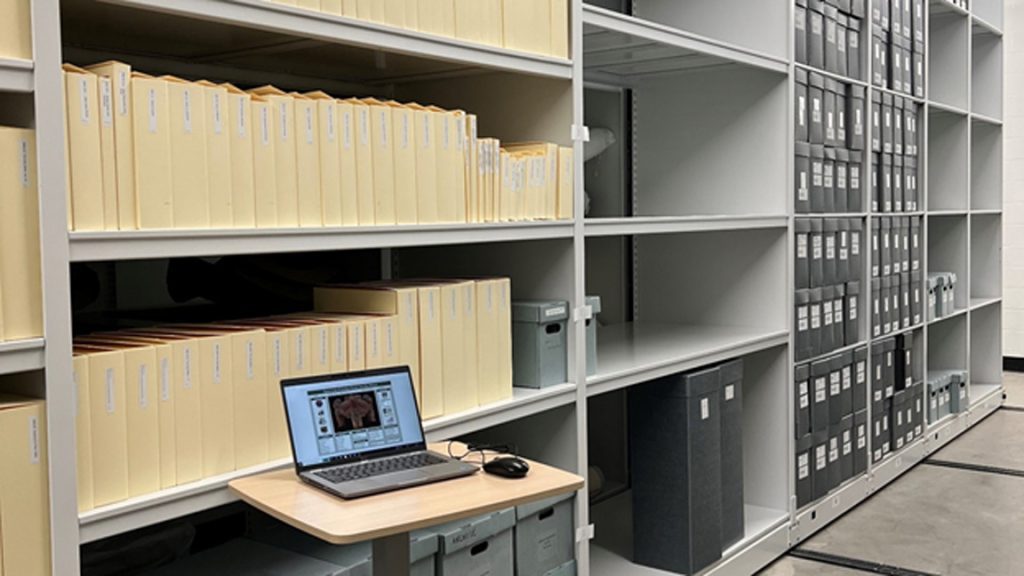

Digitization is one of the perks of modern archival research. The wonders of technology allow us to scan materials and make them available to anyone, anywhere in the world within a short span of time. We are increasingly making our archival materials available online via Internet Archive’s website. If you’re not familiar with Internet Archive, it’s a huge digital library, that is kind of an archival “cloud” where libraries and institutions can make their digitized collections available to the world. Both APH and AFB’s Helen Keller archive have collections materials available on Internet Archive. It’s an efficient and inexpensive way to make our materials available online.

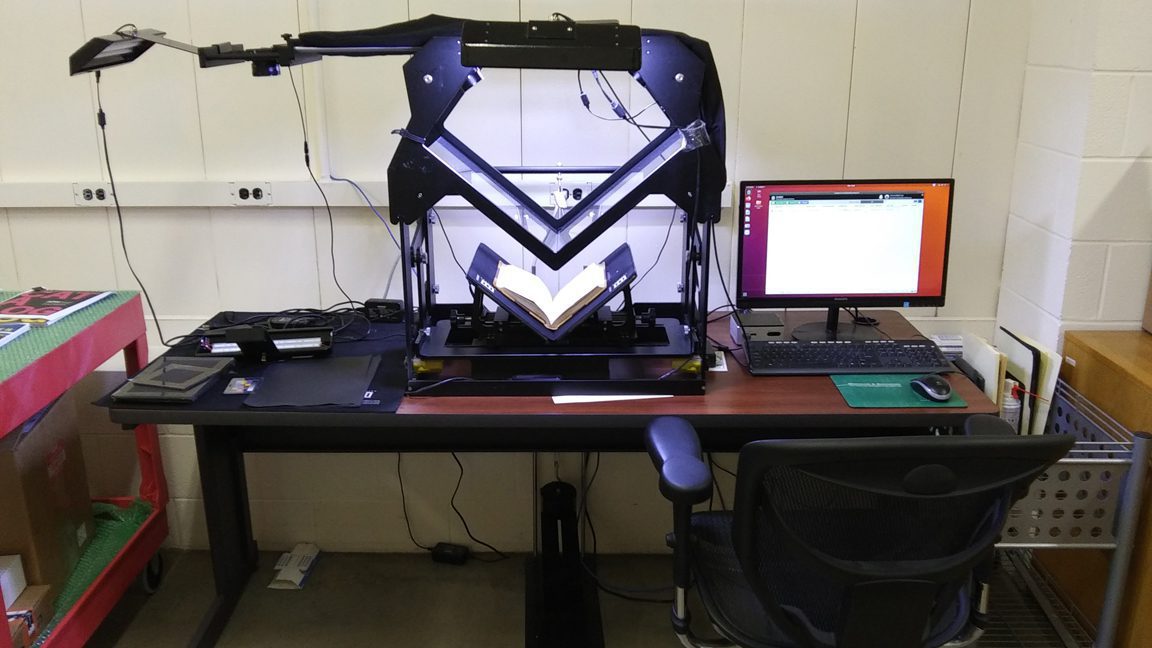

For digitization, we can send materials to Internet Archive to be scanned and uploaded by their staff—which we do for larger collections—or we can scan individual books on site ourselves. APH is very fortunate to have a specialized scanner known as the Table Top Scribe. The TTS (as it’s known in-house) is a large V-shaped contraption that is designed specifically for scanning books. Just place the book in the cradle and, using a foot pedal, raise the cradle so the book pages sit flush beneath glass panes. There are two digital cameras angled to capture both pages simultaneously, and these photos are uploaded to the attached computer. These scans are then uploaded directly to the Internet Archive, where their staff crop the images and make them available online.

In the past year, I’ve gotten several requests to digitize materials that weren’t yet available online. I received a training lesson on the TTS (courtesy of my colleague Justin Gardner, the AFB Helen Keller archivist) and I started uploading materials. There was definitely a learning curve—especially with using the foot pedal to smoothly lift and lower the book cradle, and figuring out how to best align the pages to not cut off the margins. But after a few minutes I got the hang of it and it was pretty smooth sailing. It’s been fun using the TTS and it’s exciting to think that something I’ve scanned will be available for free public access worldwide.

I’m also excited to see how these digitized materials may inform the scholarship that researchers are conducting. At our recent symposium the Hidden Legacies of Helen Keller, the final session featured university professors and graduate students who are all doing research in the field of disability history. In their remarks they made frequent reference to the archival materials that were available digitally, and how useful that access was to their research. One scholar said that, with in-person research severely limited during the height of COVID-19, online archival materials were instrumental to her dissertation research. She also shared those online resources with her fellow history students, adding that some of them then shifted the direction of their research toward a more disability history focus as a result of the digitized materials that were available to them. I look forward to seeing what scholarship comes from these emerging historians, and the field can only benefit from the fruits of their research.

This is one of the benefits of archives increasingly making their materials available online—anyone can access them anytime, anywhere. And the more people we can reach with our collections, the better for everyone. After all, we have these amazing materials in our collection and we want people to have access to them, whether in person or virtually.

Mary Beth Williams is the Museum Collections Manager at the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

Cross-Cultural Collaboration: An Interview with Dr. Elyse Connors on Her Fulbright Trip to Lagos

International efforts in blindness often involve cross-cultural collaboration to address critical gaps in services and training. We had the pleasure...

Running a Marathon: Moving a Museum Collection

With the Dot Experience at APH officially breaking ground, we have been incredibly busy behind the scenes preparing for construction...

Finding Sadie

“The blind veterans here in the Helen Keller class are able, thru talking books, to obliterate the tedious hospital hours...