To ensure gift delivery by 12/25, please place orders via UPS shipping no later than 12/17.

CloseMapheads

I’ve been a maphead all my life. When I was a kid, I drew maps in crayon of the various neighborhoods I lived in, I fastened the maps that came in National Geographic magazine into a giant scrapbook, and I traced the routes my family took on vacations and relocations in each new issue of the Rand-McNally road atlas. When I was older, history and maps merged; I was fascinated by change over time. Today, historic maps are hung in every room of my house. My office? Tactile maps on every wall and tactile globes atop the bookcase. Obviously, deciding to highlight the Museum’s map collection in our April social media was that sweet spot for me where joy and duty meet.

We have more than 150,000 objects, documents, and photos cataloged in our online archive. Hundreds of those are maps. (I swear I’ve looked at every one.) Our oldest is also the first to be printed in North America: an atlas of the world that Samuel Gridley Howe had embossed for the fledgling New England Institute of the Blind (now Perkins) in 1836. Dr. Howe railed against the tactile maps he saw in Europe, “hardly worth the name of maps,” he wrote, what with “their bits of pasteboard and string.” They contained “no lettering, no printed information, so the blind could not use it on their own.” Never the kind of person to sit around, Howe set to work, figuring out how to emboss maps and how to produce them in quantity.

There wasn’t much more information about this world atlas of his in our archives, so I went online. I couldn’t find it. Histories of tactile maps didn’t include it. A Boston-based rare book dealer claimed it didn’t exist. But it does. We have it. And so, as it turns out, do Perkins and the Huntington Library In California. Still, it’s very rare. It seems Howe discouraged the use of the 1836 atlas because he preferred his 1837 one, which he produced with the printer Samuel Ruggles. It was, as he wrote in its introduction, “far superior to that first published and composed by me.”

I know, I know. This is really geeky. But for those of us who revel in history, it’s exciting. Something new. About the past.

I love relief maps, and they’ve been around for thousands of years. Experimentation with tactile maps specifically for the blind seems to begin with Georg Weissenbourg in 18th century Mannheim (now in southern Germany). He made maps with copper rounds for towns, different textures of sand for land, glass for rivers and seas. Beautiful, but they weren’t really useful. Maria Theresia von Paradis, the Viennese composer and pianist, had dozens of maps made with beads and embroidery silks for her European tour in 1783. In 1817, Samuel Guillie, the director of Paris’s school for the blind, explained the modern way of making tactile maps. He outlined geographic boundaries with wire on cardboard, then glued on another thinner cardboard layer to hide the wire — the paste and string that annoyed Howe so much.

I thought I might find some references to maps in the accounts of James Holman, the 19th century “blind traveler,” said to have been the most prolific traveler in history. Holman was an English naval captain, and when he lost his sight in his twenties, he saw no reason to give up wandering the world. First, in 1819, he took the Grand Tour of Europe, mostly on foot, mostly by himself. He scorched the tip of his cane in the lava flow of Mount Vesuvius. He went to the Vatican sculpture garden, which was off-limits to touch, but he made friends with fellow art lovers who cued him when the guards weren’t looking. Back in England he wrote a book, a best seller. He wrote a second book, in 1825, about his treks through northern Europe and Asia. When he set off to cross Siberia, he kept his journey secret because the Russian authorities didn’t take kindly to Europeans wandering through what was essentially a large open-air prison.

Now, my adventurous moments were decades ago, and I prefer to travel in 21st century comfort, but I felt this sharp pang of kinship with Captain Holman when I read he had a tactile map of Russia among his few possessions. When he knew no one was watching, he liked to unroll the map and run his finger across the route he planned to take, tracing again and again the tips of the Ural mountains, the vast tartar steppes of central Asia, the swell of the highlands by Lake Baikal. Ah, I thought. Another maphead.

Yes, today phones are invaluable for pinpointing where we are and directing us somewhere else. But sometimes, you need your fingers to find the way, to make the journey real. No worries. Technology keeps up with tactile maps too. TMAPS, a program of the San Francisco Lighthouse for the Blind, makes tactile maps on demand. They’ll emboss one of your own neighborhood or of the Champs Elysees, Kathmandu, or the bustling city of Irkutsk by Lake Baikal where James Holman survived a frozen captivity and was then unceremoniously escorted back to the Polish border. The maps used to be free, but demand exceeded expectations, and now they cost $25.00 each. For that, you get two maps, an overview and a close-up. Worth it.

Share this article.

Related articles

Blindness History Basics: Helen Keller Archival Collection

One of the most fascinating treasures at The Dot Experience is the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) Helen Keller...

A Token of Japanese American Friendship

Even a simple inquiry about one item in an archive can have a surprising number of highs, lows, twists, and...

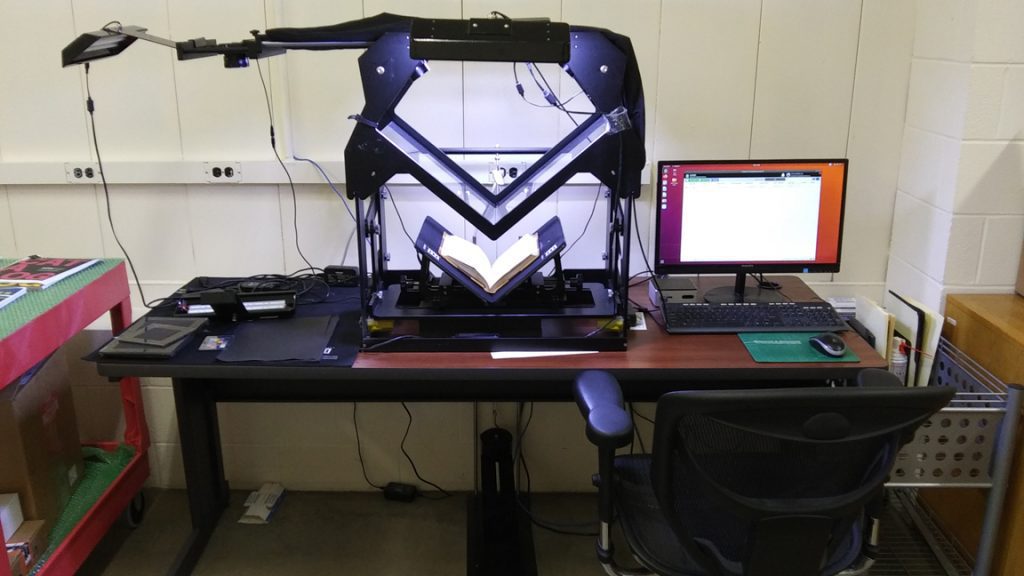

Online Archives in a Digitized World

Have you ever done research in an archive? Maybe for a school project, or just researching a topic of personal...