Why eBraille is a Braille-Based Document Type

One of the biggest early questions about eBraille was whether the standard would be print-based, like DOCX or EPUB, or braille-based, like BRF or PEF. Both approaches are used today so it’s possible to know the benefits and drawbacks of each approach. This question was much discussed when the process of creating eBraille started and it’s important that people know why we took the approach that we did.

Translated automatically via a screen reader or braille display, there are many advantages to utilizing print-based file types. These file types usually require less training than a braille-based file type, which requires knowing braille and braille formatting. The translation is handled using tables that are usually provided either by Duxbury or LibLouis, which are usually very good. When there is an issue with the translation, it is typically because of the quality of the file being translated.

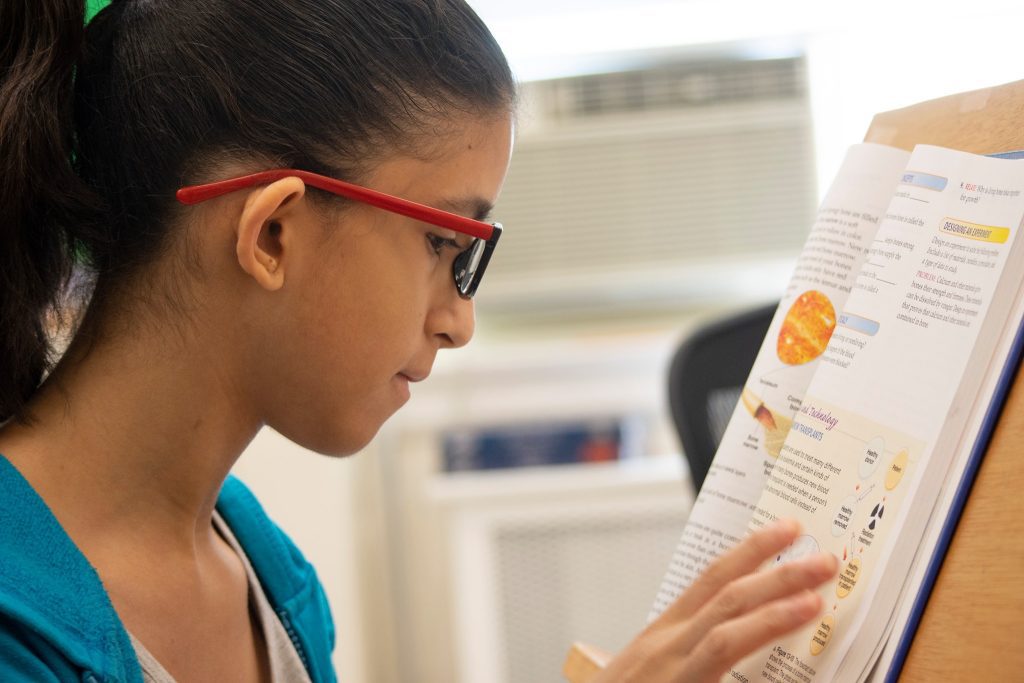

The most obvious problem is that sometimes print-based materials, especially those that are prepared by the publisher or by an entity that is not familiar with the requirements of braille, will use pictures of text instead of text. Used instead of a set of materials like a timeline, or in place of diacritical marks or mathematical notation, this material is often inaccessible to whatever software is handling the translation and will be skipped in the automatic braille rendition.

The main problem, however, is proper translation of technical material like science, math, and chemistry. Requiring precise representations of the information that needs to be translated often means utilizing MathML or other similar methods for describing mathematical notation, like LaTeX. However, creating MathML and LaTeX often requires even more training and can take more time than just providing the correct braille translation.

An additional problem with relying on an automatic translation is that translation tables receive updates which aren’t always applied to the hardware and software that is processing the translation. This can lead to a situation where one person is using one kind of hardware and getting one translation of the material, while another person is using a different kind of hardware and getting a completely different translation. This may be fine for casual reading, but it can be detrimental for high stakes situations like tests, textbooks, and other educational activities. Automatic translations are also insufficient for music and the availability and quality of tables varies throughout the world.

While there are drawbacks to print-based materials, we could potentially correct them by having people help to correct issues that are identified. The problem is that there are braille regions that already utilize this basic system and the results don’t really change outcomes for students. In some European countries, they provide each student with a single-line braille display and then give them digital print-based versions of their textbooks and hardcopy tactile graphics. This system then leads to costs and delays that are comparable to what we have in the United States with our braille-based system.

It is for all these reasons that the working group pursued a braille-based system. By making eBraille a primarily braille-based document type, we’re keeping an emphasis on the need for a correct, precise, and consistent translation. We’re also using a workflow and the talents of the same transcribers, teachers, and braillists that have been providing braille to braille users for many years, so that we don’t have to create new software, methods, or workflows just to accommodate the file type.

eBraille will be another option going forward. Adult braille users will be able to decide for themselves whether they would prefer an automatic translation with a print file, a formatted braille document like BRF, or the new eBraille file type. Students will benefit from these same options.

The important thing is that we keep making braille available by whatever means are available to us. Braille is not going away. If anything, it is only going to become more readily available and less expensive as we continue to take advantage of the latest technological innovations. Let’s keep making braille!

Share this article.

Related articles

Louis and the AMP Database: Supporting Students and the Field

The Louis Database The concept of sharing information between braille-producing agencies dates back to the 1950s, when APH used a...

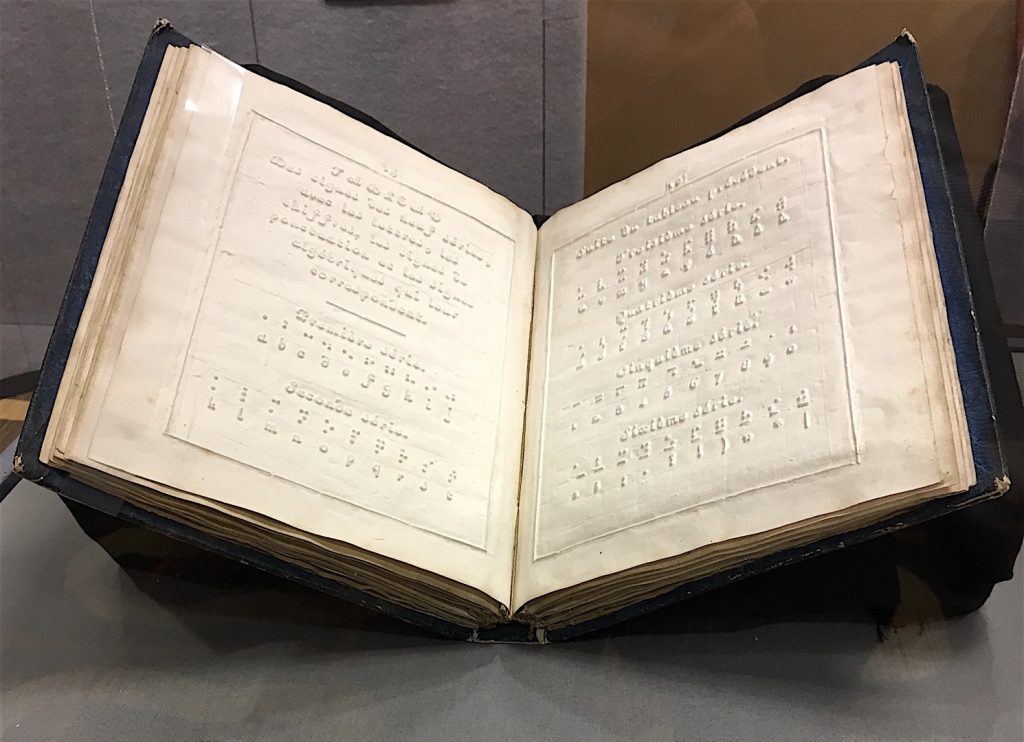

Blindness History Basics: The First Publication of the Braille Code

Louis Braille’s code lives on today as individuals who are blind and have low vision use his system to read...

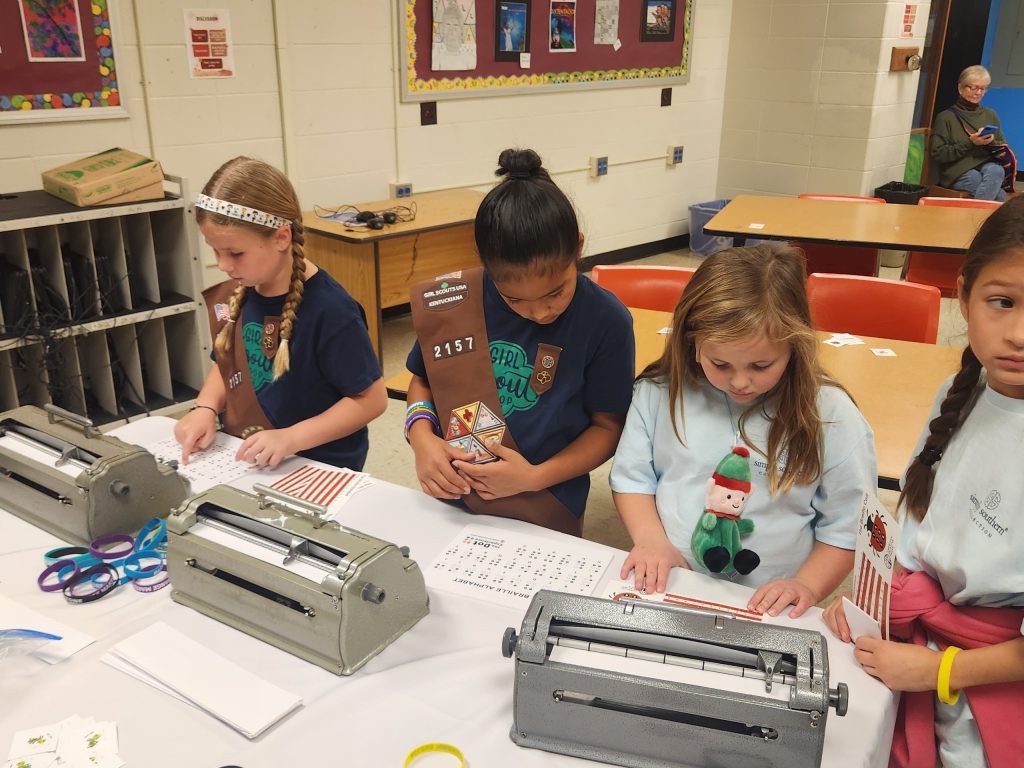

Literacy Through Touch: Introducing Braille with The Dot Experience Programs

The six dots in The Dot Experience logo represent the structure of the braille cell, an important code that makes...