We Should Not Forget: A Black History Month Profile of Vince Male

A Museum guest blog by the Rev. Dr. Eugene A. Bourquin

Sometimes our history – our heroes – slip away into posterity without notice. We should not forget.

The Industrial Home for the Blind (IHB, now Helen Keller Services) holds a special place in the history of blind and Deafblind Orientation and Mobility. And from the IHB, we know Vincent “Vince” Male, a Black American O&M Specialist, who pioneered Deafblind independent travel. Vincent Male was born on April 11, 1937, in Jamaica, Queens, New York. He died on April 10, 2012, in Westbury, New York, at the age of 74. IHB was probably where the idea of assisted street crossings using a communication card first began. Former IHB director Harold Richterman believed that Vince might have been the first person to teach the use of street crossing assistance cards to travelers who were Deafblind as early as the 1940s. In August of 2006, I had the opportunity to interview Vince about his experiences with travelers who are Deafblind.

There are few references to formal instruction in independent travel for children or adults who were Deafblind before 1979. That year, Vince, completing a Master’s thesis (An Approach to Teaching Deaf-Blind Individuals) at Hunter College in New York City, described a system of orientation and mobility for people who are Deafblind. He was the first certified mobility specialist known to write about this. Not until 1988 would the subject be substantially addressed in a peer-reviewed national journal (DeFiore & Silver, 1988).

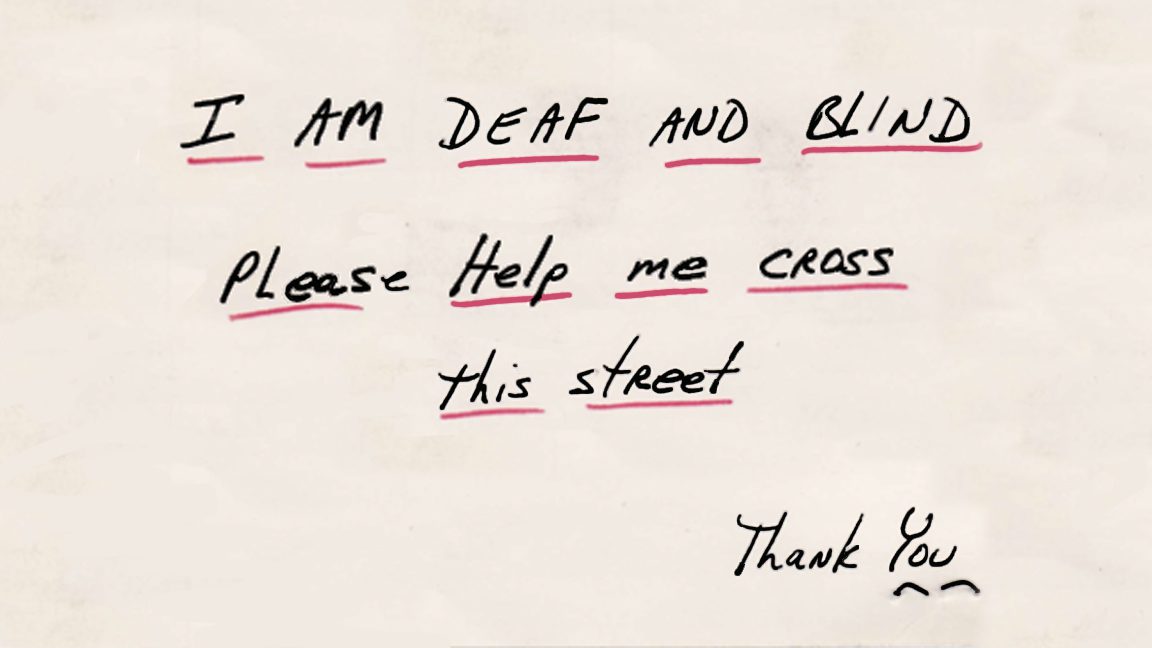

Vince addressed street crossing for pedestrians who could not produce understandable spoken English. He recorded in detail the use of a printed card system that could “efficiently, effectively, and accurately communicate their needs to the public.” This is a methodology still in use three decades later. The cards read:

I AM DEAF AND BLIND

Please help me to cross the street.

Thank you.

TAP my shoulder if you understand

In the left corner of the card, a hole was made to inform the person who was Deafblind that she or he was holding it correctly, in a manner that was easily read by the potential helper. In order to attract the attention of the public, the traveler tapped his or her cane against the perpendicular curb several times to create a noticeable noise and repeated this at intervals when necessary. With this methodology fully articulated, most of the essential elements of assistance-gaining were established: a card to communicate with the public which explained what the traveler needed and which specified a confirming response.

Significant work on improving crossing cards and communication with the uninitiated public would follow, but it was Vince Male who began a path to independence that open the world to many.

Gene Bourquin is an Orientation & Mobility specialist, low vision therapist, and ASL/English interpreter working in New York City.

Share this article.

Related articles

Piney Woods Country Life School

For a small exhibit this fall I researched two Hall of Fame recipients, Dr. Laurence C. Jones and Martha Morrow...