From the Archive: Reparative Description and the Power of Language

Note to the reader: this blog contains outdated historical terms for schools for the blind which are now deemed offensive.

After a recent conversation with a visitor about Helen Keller’s childhood, I began reflecting on her “water pump moment” with Annie Sullivan. And how in that moment at the water pump Annie not only taught Helen the name for water but unlocked the power of language, language which Helen then skillfully crafted throughout her life to write books, letters, give public speeches, and engage with countless people on her world travels.

Language can be incredibly powerful, and it is constantly evolving. The words we use can have a profound impact—for both good and ill. The archival world, like so many aspects of American society, is also undergoing a much-needed reexamination of its practices and how they have—whether unintentional or not—caused harm to any number of groups. As such, there is a movement in archives toward reparative description. I am admittedly still learning how to best implement this important concept in my work at APH, but the idea behind reparative description is, in essence, to do no harm in your description of archival collections.[i]

Archivists try to be neutral parties, but the fact is, we are human and can unintentionally impose our biases onto how we process or describe collections—which can then have an impact on a researcher who is using those records. In years past, descriptions of collections may have highlighted males, or white people, or had colonial, racist, sexist overtones. Women might have been listed as “wife of Mr. Macy,” or “Mrs. John A. Macy” (as Annie Sullivan’s name was often written) rather than being referred to by their own name. Enslavers’ role in human trafficking and bondage may have been glossed over or omitted, with the description focusing instead on their civic activities. These are very generalized examples, but give you the idea of why older, legacy descriptions can often have a need for a modern reexamination and rewrite.

Sometimes encountering harmful language in historical records can’t be avoided, and so it must be contextualized by the era in which the materials were created. In my time working at APH, I’ve come across some historical terms about the disabled community that are truly offensive by today’s standards. When researching a Hall of Fame recipient, I discovered that he attended a “School for Defective Youth” (I think my jaw dropped to the floor when I read that one…). In looking through old Commissioner of Education reports ranging from 1870 to 1915 I encountered numerous schools for the “Deaf, Dumb and Blind” (“dumb” at the time referred to someone unable to speak). Helen Keller was even referred to as such in a 1912 New York Times article, printing that “Miss Helen Keller, born blind, deaf and dumb, has learned to sing. It was the wonderful girl herself who announced it — and over a telephone, at that.” These outdated, offensive, and ableist terms, while commonly used in the past, must be navigated with care by archivists today. We can’t erase or edit the past. But hopefully, through reparative description, we can give voice to marginalized groups who may have been overlooked or oppressed in the past.

Helen’s water pump moment became a catalyst, providing the young girl with vital access to language. And Helen’s inherent intelligence, combined with Annie Sullivan’s guidance and support, transformed her from that unruly child to a college graduate, celebrated author, humanitarian, and activist whose voice had global reach. As a young deaf-blind child she may have lacked the ability to speak, but Helen was certainly never dumb.

[i] The Society of American Archivists’ Dictionary of Archives Terminology defines reparative description as:

remediation of practices or data that exclude, silence, harm, or mischaracterize marginalized people in the data created or used by archivists to identify or characterize archival resources.

Mary Beth Williams is the Collections Manager at the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

Blindness History Basics: Helen Keller Archival Collection

One of the most fascinating treasures at The Dot Experience is the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) Helen Keller...

Connect the Dots: Celebrating Helen Keller

We celebrated a very special woman at the Saint Matthews Eline Library on June 15. Born on June 27, 1880,...

Defining The Dot Experience: Everything You Need to Know

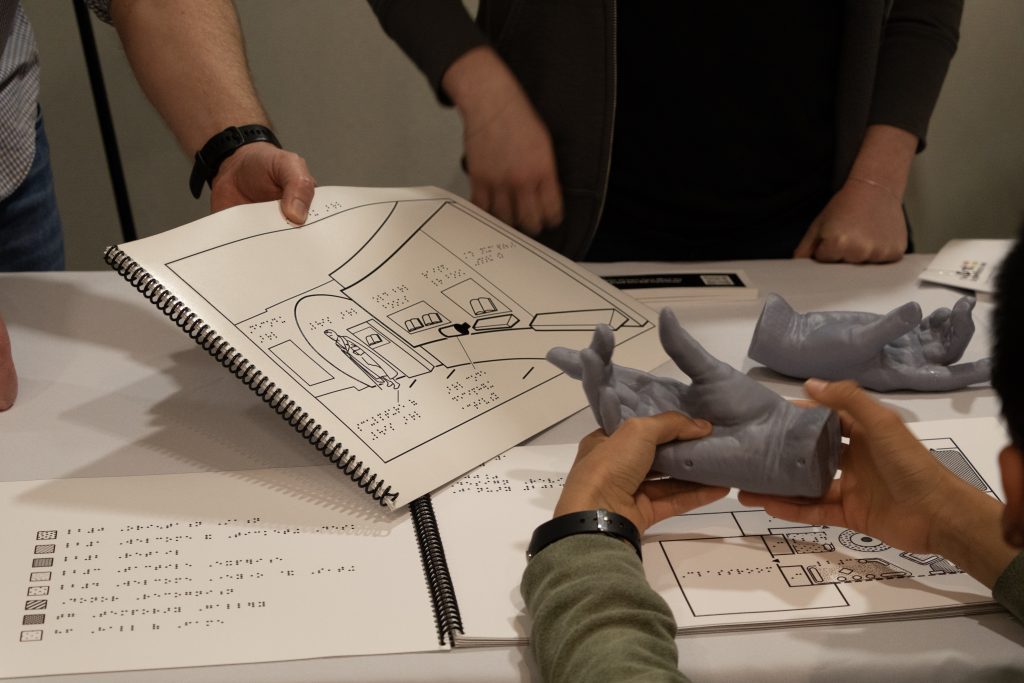

What is The Dot Experience? The Dot Experience is APH’s re-imagined museum set to open in 2026. Designed with an...