Blindness History Basics: History of Braille Writers

When fifteen-year-old Louis Braille presented his tactile system of raised dots in 1824, he hoped the new system would provide a simpler path to literacy for blind people; an easier way to read and write. The dot system named after Louis proved an immensely successful tool, enabling people using braille to read as quickly as print readers. The system also offered the most effective writing method known for people who are blind or low vision. In Louis’ day, writing was slow and laborious compared to today, whether you used paper and pen or his new dot system. The young inventor could not have envisioned the machines and technology that would, eventually, create tools to help his system of six dots transform communication for people who are blind or low vision.

Louis Braille punched a stylus into a slate to work out his code. The slate is a simple device, originally made of two pieces of wood or metal hinged together on one end. Writers insert heavy paper between the hinged pieces. Cells on the slates guide writers as they push down with their stylus to create an indentation. In order to read the words from left to right, a slate user has to write backwards and mirrored, so when the paper is turned over the dots read in the correct order. Although using a stylus seems time consuming today, it was revolutionary at the time, and was the best method available until the machine age. Numerous companies worldwide manufactured these simple devices. APH began producing wooden and metal slates and styluses in the 1930s and continues to offer a plastic version today. The quest to create a better device to help people who are blind or low vision write quickly and easily, however, began before braille became the universal code for people who are blind or low vision.

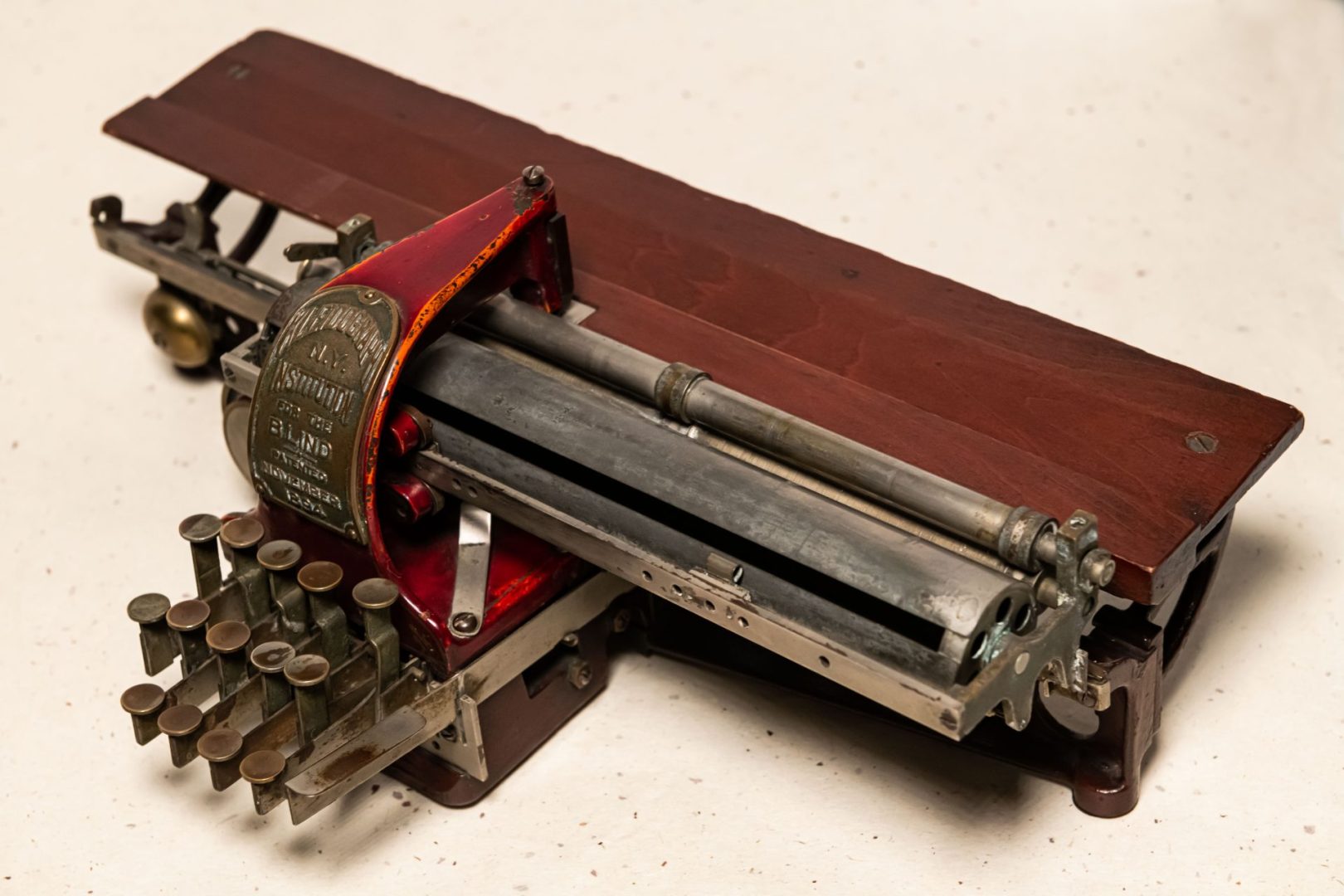

During the War of the Dots, inventors created devices to help people write in many of the competing codes. McElroy’s Point Writer (1887), and the Kleidograph (1894), were both designed for New York Point. APH purchased the rights to McElroy’s Point Writer in 1887 and produced 47 of the devices in 1888. In 1890, Illinois School for the Blind Superintendent Frank Hall delivered the prototype for the first braille writing machine based on typewriter design. The American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) purchased the design and production equipment for Hall’s Braille Writer in 1930. AFB discontinued Hall’s Braille writer when its own machine, the Foundation Writer, went into production in 1932. AFB produced approximately 2,000 Foundation Writers between 1932 and 1947, when it went out of production. Like most early braille writing machines, Hall’s Braille Writer and the Foundation Writer were heavy; their many moving parts were easily broken and difficult to repair. In the early 20th century, Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts, based the design of their braille writer on Hall’s concept. The machine was heavy, not very durable, and needed frequent repair. Perkins director Gabriel Farrell halted production of the machine in 1931, determined to create a machine that was not limited by the design issues of its predecessors. Farrell asked David Abraham, an employee of the Perkins Industrial Arts Program, to create a prototype of a braille machine with specific desirable features. Abraham spent the next five years working on the machine in his basement and brought the prototype to Farrell in 1941, as America was entering World War II and national restrictions on manufacturing refocused machine production across the country.

After World War II, Perkins and AFB trustees, convinced Abraham’s machine was superior to any other, worked together to finance and produce the machine. Loans secured by the two organizations allowed the first 2,000 Perkins Braille Writers to be produced for a cost of $70 each. Originally offered for sale in 1951, the Perkins Braille Writer is still in production. Today, the Perkins is the most widely used mechanical brailler in the world, with more than 375,000 machines distributed in over 170 countries. Today, most new devices to help people who are blind and low vision write are based on technology, but the durable Perkins Brailler continues to be a valuable tool for achieving literacy.

Share this article.

Related articles

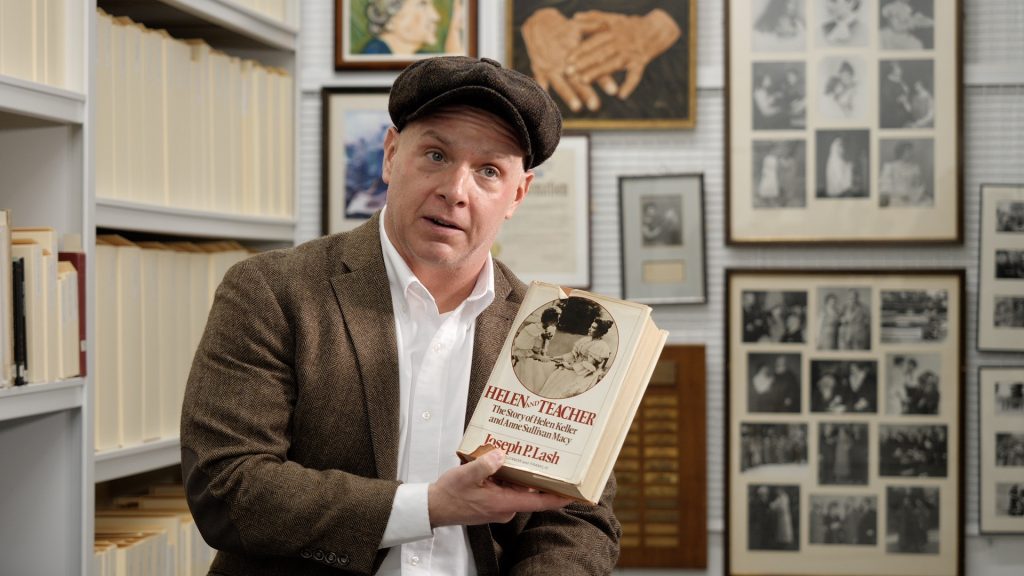

Unveiling a Legacy: The Helen Keller Time Capsule

Around the corner from the heart of braille production and product storage, sits a room tucked against the back wall...

Tiny Explorers, Big Adventures: Fabled Friends Recap

On Saturday, February 22, The Dot Experience Team, along with APH staff and volunteers, joined the fun at the Fabled...

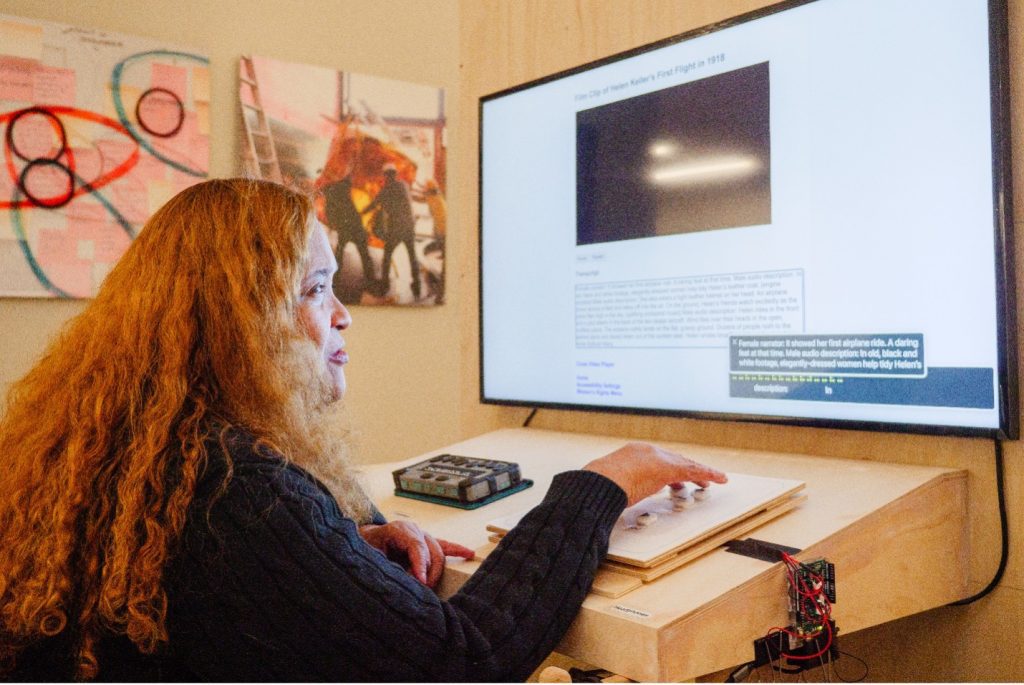

Creating Inclusive Museum Experiences: The Role of Media Integration in The Dot Experience

We recently had the opportunity to talk with Billy Boyd and Annie Schauer from Solid Light to learn more about...