Please be advised USPS is experiencing unusually long delays for Free Matter For The Blind shipping. If you have not received an order placed more than 30 days prior, please contact the APH Customer Service team at support@aph.org or 1-800-223-1839.

CloseBlindness History Basics: A Brief History of the Refreshable Braille Display

Braille, introduced by Louis Braille in Paris, France in 1829, has opened up the world of reading and writing for people who are blind or low vision. The system isn’t perfect, however, and in its ordinary form, paper braille is bulky. Print documents need to be transcribed into the braille code, which can be time consuming and expensive. Enter the portable refreshable braille display on a device that can allow a user to store, read, and write documents. Braille users employ them today in many forms, but how did they get started? The first working display recorded in our files at The Dot Experience is a device developed first by James Bryce at International Business Machines (IBM), around 1950, and then later worked on by Arnold Grunwald at the Argonne National Laboratory. This device stored information on perforated paper tapes. It created raised braille characters on a plastic belt that moved under the reader’s fingers at their chosen pace.

By the early 1970s, other early braille displays were electro-mechanical, using solenoids—essentially powerful miniature magnets—to raise and lower pins to create braille. Data was stored on cassette tapes. In Germany, Werner Boldt introduced his “Braillex” and Klaus Peter Schonherr was working on the problem. His company would later become Handy Tech. In Great Britain, John Clarke was experimenting with his Brailink device.

The real breakthrough occurred when Oleg and Andie Tretiakoff introduced the first commercially available paperless braille machine in 1976 in Paris, France. Their Digicassette stored data on cassette tapes and displayed it on a bar that raised and lowered pins to create and erase a line of braille at a time. Tretiakoff pioneered the piezo-electric display technology that dominates the market even today, using the principle that some materials change shape when zapped with small electrical charges. Tretiakoff took his idea to the American company Telesensory, hoping to partner with them to get his device into the American market. Instead, Telesensory introduced their own device in 1979, the Versabraille, also a portable device that stored data on cassette tapes and featured a 20-cell refreshable braille display. You could use the Versabraille as a notetaker, entering and editing data using its braille keyboard; a reading machine, reading braille documents on the display; or as a computer terminal, attaching it to a desktop computer and reading braille rather than looking at a computer screen.

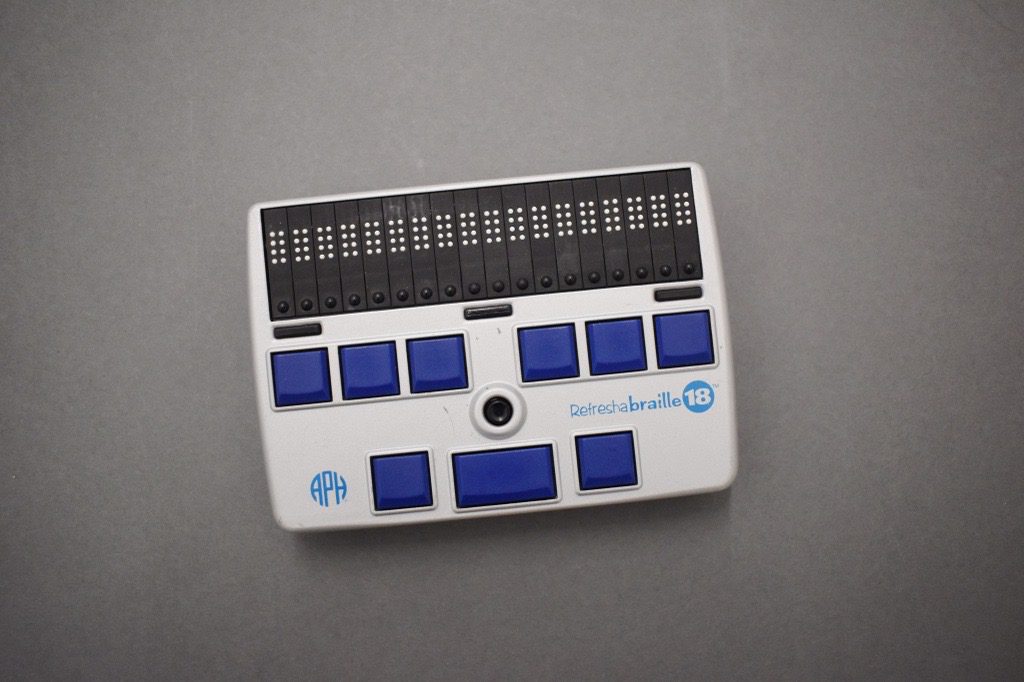

For much of the last fifty years, refreshable braille development has simply been a refinement of Tretiakoff’s ideas. Using transistor technology to miniaturize the devices, people have played around with the number of braille cells in the display—as few as 16 or 18 on a small device and up to 40 on true braille terminals, adding or subtracting applications on devices to turn them into true pocket computers with a wide array of capabilities. There are many refreshable braille devices on the market from many manufacturers, but until recently, all continued to rely on variations of Tretiakoffs piezo-electric cell. Remaining expensive to this day, those cost around $250 per cell.

In 2011, a number of international blindness agencies banded together to form the Transforming Braille Group, pooling their resources to reduce the price of refreshable braille displays. The goal was a display that would sell for under $500, making it affordable for people around the world. The result was a partnership with Orbit Research, a company headquartered in Wilmington, DE, and a device called the Orbit 20. The Orbit 20 relied on a completely new design, called the micro-machine, to raise and lower its braille pins, and the device cost around $600. In its initial form, the Orbit 20 was a low function notetaker and reading machine, but today Orbit sells several shapes and functions.

The true holy grail was always a full-page, refreshable braille device that could also display tactile graphics. APH has been working on this challenging prospect for almost 14 years. During that time other makers—see Bristol Braille’s Canute 360 and Orbit’s Graphiti®—introduced multi-line displays. The Canute is interesting, creating braille symbols by rotating and raising wheels crafted with portions of the braille cell around their periphery. With the introduction of the Monarch from APH and Humanware, a revolutionary multiline braille display device, long held dreams and wishes have become reality. The Monarch combines a reliable multiline braille display with tactile graphics capabilities that stretch what is possible in a single device. It’s pretty exciting and another step in what has been a long journey of invention.